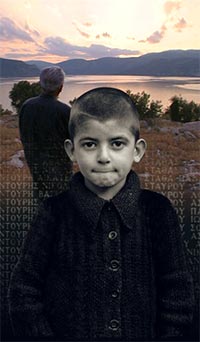

Argyris Sfountouris

Early childhood

Argyris Sfountouris was born in Distomo (Greece) in 1940. After three daughters, his parents were pleased to have a son, and so was his grandfather because his grandson was traditionally baptised with his name, Argyris.

In April 1941 the German Wehrmacht invaded Greece. As a result of the occupation, a devastating famine ravaged the country, particularly the cities. However, farming families in villages far away from the cities managed to get by. But on June 10, 1944, Distomo was seized with horror. After the soldiers of a German SS special division had blocked off all access to the village, a so-called retaliatory measure was initiated: to avenge a few fellow-soldiers, who had died in a fight with Greek partisans near a neighbouring village, the German soldiers first shot twelve farmers and then killed the villagers. They murdered more than two hundred inhabitants: babies, children, pregnant women, and elderly people. Argyris lost his parents and thirty more relatives. The massacre, which took place only four days after the Allied landing at Normandy (June 6, 1944), is considered one of the most atrocious of its kind (cf. Appendix A).

At the orphanage

The boy, who was not even four years old, was put in an orphanage at Piraeus, accommodating more than a thousand war orphans. As he was only skin and bones, he was transferred to a smaller orphanage on the other side of Athens. But despite better and more individualised care, he was barely able to digest the food because he suffered from a stomach complaint.

The external threat was by no means banished: while World War II was coming to a close, Greece was ripped apart by a long and bitter civil war between left-wing partisans and right-wing paramilitary units that were close to the government and supported by the British and later by the Americans, for the Communists were to be prevented at all costs from becoming the strongest force in the country. First harbingers of the Cold War.

Meanwhile a Red Cross delegation paid a visit to the orphanage. They selected a number of children, 8 ½ year-old Argyris among them, that were to be sent on a journey to a faraway country: to the Pestalozzi Children’s Village in Trogen/Switzerland. To a home with Greek house parents and Greek war orphans, to a village with children from all over Europe, to an “intact” country, to a new future.

A new home far away from home

Post-war Switzerland considered the Pestalozzi Children’s Village the embodiment of a Swiss ideal: putting into action humanitarian commitment, providing help, healing war wounds, and encouraging cohabitation and reconciliation between various ethnic groups in the heart of Europe. After fierce initial opposition, a German house was finally built next to the Polish, Hungarian, Greek, Italian, English and French houses. It was first headed by Swiss director Arthur Bill. German children were tolerated, but German adults were admitted to the village only years later.

As Argyris was slowly regaining strength, he was noticed for his extraordinary brightness. He went to Trogen grammar school and, after his A-levels, to ETH Zurich (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology) where he studied mathematics, nuclear physics and astrophysics.

As a young physics teacher, Argyris started to write poems and essays. The German language had become a second nature to him. When visiting his native village, he was silently reproached for being a traitor... He also started translating Greek poets and writers (Kazantzakis, Kavafis, Seferis, Ritsos and many others) into German. His translations, book reviews and obituaries were regularly published in the NZZ, in “du”, the Tages Anzeiger and other periodicals.

The military dictature in Greece

In 1967, colonels staged a coup in Greece. A brutal military junta was set up. Over the following seven years, more than 100,000 Greeks – dissenters, intellectuals, writers, musicians such as Mikis Theodorakis, and Communists – were persecuted, shipped to isolated islands prisons, incarcerated and tortured. Barely a month after the junta was set up in Greece, Argyris and a group of students and politicians organised a rally in Zurich called “Against the Greek Dictature”, where Max Frisch and August E. Hohler gave speeches. He published the cultural magazine “Propyläa“ containing poetry and works that were prohibited in Greece. He saw it as his way of fighting for the restoration of democracy in his home country. For this endeavour, he received an honorary award from the Zurich senior executive office in 1970. Thanks to a telephone call from a cousin, he cancelled a planned trip to Athens at the very last moment. Otherwise he too would have fallen victim to the military’s political purge.

For he was on a black list in Greece. The Greek embassy in Zurich no longer renewed his passport. He did not have a Swiss passport because former inhabitants of the Children’s Village were supposed to return to their home country as adults. He could not travel anywhere anymore. Switzerland, his host country, had become his exile. So he applied for naturalisation, which was granted only 52 months later because Switzerland now kept a file on the young man as well.

The cosmopolitan

At forty, there was a radical change: Argyris decided to become a development aid worker. After taking a Master of Advanced Studies in Development and Cooperation (NADEL) at ETH Zurich, he spent several years in Somalia, Nepal and Indonesia, where he took part in a project setting up advanced technical colleges. He would later call those years the best of his life. “...as if the past and all the tragic events I had gone through were somehow suspended. At least they were not rejected, tabooed or repressed. They belonged to my life without being painful.”

Reunification – Reparation payments

Upon his return to Europe in 1990, the Berlin Wall had fallen. The German reunification caused a new, rather delicate legal situation. Almost fifty years after the end of World War II, reparation payments could be claimed for the damage suffered in the war (cf. Appendix B – Legal background of the Greek reparation claims).

“Congress for peace”

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Distomo massacre in 1994, Argyris and the community of Distomo organised a “congress for peace” at the European cultural centre in Delphi. The congress topics “Remembrance – mourning – hope“ looked at the efforts made in Germany, Greece and elsewhere as regards compensation, defeating hate, and reconciliation. The congress was attended by nineteen speakers: historians, journalists, brain researchers, social education workers, psychoanalysts, resistance fighters, youth workers, and lawyers from Athens, Zurich, Berlin and other cities. Research results were exchanged, conditions for peaceful cohabitation and reconciliation discussed and the psychological causes leading to such inhuman deeds debated. However, one group was not represented: despite great efforts and repeated requests, not one German politician, not even the German ambassador in Athens, agreed to participating at the congress. A bitter disappointment for Argyris.

Being aware of the volatile nature of the German reunification agreement, he paid a visit to the German embassy in Athens. He asked how best to formulate his claim for compensation for the damages suffered in the war. He received a written reply from the embassy in 1995. It stated that the massacre was to be considered as a “warfare strategy” and that, as a result, no compensation could be claimed. He was deeply hurt by the fact that the significance of the massacre was still not recognised to its full extent, but was played down instead.

Court appeals

Together with his three sisters, Argyris decided to bring a charge against Germany. In parallel, a collective claim was filed in Greece by 290 directly affected people, relatives, and descendants in Distomo.

For Germany the matter was extremely “delicate”. In case Argyris’s appeal or the Distomo collective claim came through, this could cause a breach in the dam, flooding the German Federal Republic with countless international reparation claims, which it had managed to ward off and postpone for decades.

Over the next few years, the District Court in Bonn, the Superior Court in Cologne and the Federal Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe rejected the claims, paradoxically with partly contradictory arguments: individuals could not make any reparation demands, at least not demands they themselves directed against the German state. On the other hand, individuals could in principle assert claims for their own person in relation to war crimes, but if so, the legislation of 1944 was applicable, which did not provide for such claims. A constitutional complaint was filed at the Federal Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe in 2003. The decision was rendered in March 2006: it was negative. As an ultimate legal resort, an appeal was lodged at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasburg in June 2006 (cf. Appendix C.) The answer from Strasburg is still pending.

What now?

Argyris went through a tiring whirlwind of court hearings and related activities, as well as lectures at manifestations and counter manifestations. He had the frustrating feeling of finding himself a powerless victim once again. He started to doubt whether it had been worthwhile. Could the loss of his parents and his robbed childhood ever be compensated by money? A feeling of emptiness swept over him. What now?

Yet in his moments of doubt, the memory of Willy Brandt’s kneeling in Warsaw emerged. What an unusual attitude! The German Chancellor’s posture and his wordless gesture were a silent ritual undermining the traditional political code. His subsequent words: “I am ashamed” turned his highly personal feeling into a political manifestation with immense impact throughout the world.

Argyris has attained one goal at least: The Distomo massacre has reached wide public attention and has found a response he would never have believed possible. Even the Federal Constitutional Court in Karlruhe stated that the Distomo massacre was one of the most abominable war crimes. Over the years, countless personal friendships have formed with people from the Distomo Working Group in Hamburg, where Argyris also found his German lawyer Martin Klingner, who represents him in court.

Argyris is devoting his time to his own plans. He wants to go over one of his plays: “Adopting humanity“. He is working on a draft aimed at updating the Geneva Convention. Under the heading “Soldier's Honour Initiative”, the Convention is to stipulate the introduction of worldwide guidelines of soldier training. It should be a soldier's duty to disobey inhuman orders and to oppose ordered criminal acts.

Argyris is thinking about selling his childhood home in Distomo. But would anyone ever want to buy a house in a village that has never really recovered from the massacre, where life drags on, where there is a continual drift to the cities? And yet: sometimes he is overcome by a sense of longing to be able to let go of the past and, released from the weight of his memories, to be free…

For the time being, Argyris commutes between Zurich, Distomo and Athens.

Appendices

Appendix A

The events of June 10, 1944 – Memorial plaque in Distomo Museum

PDF 72 KB

Appendix B

Legal background of the Greek reparation claims

PDF 36 KB

Appendix C

Appeals to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasburg

PDF 52 KB

Appendix D

Biobliography of Argyris Sfountouris (excerpt)

PDF 84 KB